FO (complexity)

FO is the complexity class of structures which can be recognised by formulae of first-order logic. It is the foundation of the field of descriptive complexity and is equal to the complexity class AC0 FO-regular. Various extensions of FO, formed by the addition of certain operators, give rise to other well-known complexity classes,[1] allowing the complexity of some problems to be proven without having to go to the algorithmic level.

Contents |

Definition and examples

The idea

When we use the logic formalism to describe a computational problem, the input is a finite structure, and the elements of that structure are the domain of discourse. Usually the input is either a string (of bits or over an alphabet) the elements of which are positions of the string, or a graph of which the elements are vertices. The length of the input will be measured by the size of the respective structure. Whatever the structure is, we can assume that there are relations that can be tested, for example " is true iff there is an edge from

is true iff there is an edge from  to

to  " (in case of the structure being a graph), or "

" (in case of the structure being a graph), or " is true iff the

is true iff the  th letter of the string is 1." These relations are the predicates for the first-order logic system. We also have constants, which are special elements of the respective structure, for example if we want to check reachability in a graph, we will have to choose two constants s (start) and t (terminal).

th letter of the string is 1." These relations are the predicates for the first-order logic system. We also have constants, which are special elements of the respective structure, for example if we want to check reachability in a graph, we will have to choose two constants s (start) and t (terminal).

In descriptive complexity theory we almost always suppose that there is a total order over the elements and that we can check equality between elements. This lets us consider elements as numbers: the element  represents the number

represents the number  iff there are

iff there are  elements

elements  with

with  . Thanks to this we also want the primitive "bit", where

. Thanks to this we also want the primitive "bit", where  is true if only the

is true if only the  th bit of

th bit of  is 1. (We can replace addition and multiplication by ternary relations such that

is 1. (We can replace addition and multiplication by ternary relations such that  is true iff

is true iff  and

and  is true iff

is true iff  ).

).

Formally

The language FO is then defined as the closure by conjunction (  ), negation (

), negation ( ) and universal quantification (

) and universal quantification ( ) over elements of the structures. We also often use existential quantification (

) over elements of the structures. We also often use existential quantification ( ) and disjunction (

) and disjunction ( ) but those can be defined by means of the first 3 symbols.

) but those can be defined by means of the first 3 symbols.

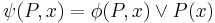

The semantics of the formulae in FO is straightforward,  is true iff

is true iff  is false,

is false,  is true iff

is true iff  is true and

is true and  is true, and

is true, and  is true iff

is true iff  is true for all values

is true for all values  that

that  may take in the underlying universe.

may take in the underlying universe.

Property

Justification

Since in a computer elements are only pointers, i.e. strings of bits, in descriptive complexity the assumptions that we have an order over the element of the structures make sense. For the same reason we often suppose either a BIT predicate or + and  , since those primitive functions can be calculated in most of the small complexity classes.

, since those primitive functions can be calculated in most of the small complexity classes.

FO without those primitives is more studied in finite model theory, and it is equivalent to smaller complexity classes; those classes are the one decided by relational machine.

Warning

A query in FO will then be to check if a first-order formula is true over a given structure representing the input to the problem. One should not confuse this kind of problem with checking if a quantified boolean formula is true, which is the definition of QBF, which is PSPACE-complete. The difference between those two problems is that in QBF the size of the problem is the size of the formula and elements are just boolean values, whereas in FO the size of the problem is the size of the structure and the formula is fixed.

This is similar to Parameterized complexity but the size of the formula is not a fixed parameter.

Normal form

Every formula is equivalent to a formula in prenex normal form (where all quantifiers are written first, followed a quantifier-free formula).

Operators

FO without any operators

In circuit complexity, FO can be shown to be equal to AC0, the first class in the AC hierarchy. Indeed, there is a natural translation from FO's symbols to nodes of circuits, with  being

being  and

and  of size

of size  .

.

Partial fixed point is PSPACE

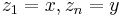

FO(PFP) is the set of boolean queries definable in FO where we add a partial fixed point operator.

Let  be an integer,

be an integer,  be vectors of

be vectors of  variables,

variables,  be a second-order variable of arity

be a second-order variable of arity  , and

, and  be a FO(PFP) function using

be a FO(PFP) function using  and

and  as variables. We can iteratively define

as variables. We can iteratively define  such that

such that  and

and  (meaning

(meaning  with

with  substituted for the second-order variable

substituted for the second-order variable  ). Then, either there is a fixed point, or the list of

). Then, either there is a fixed point, or the list of  s is cyclic.

s is cyclic.

PFP( is defined as the value of the fixed point of

is defined as the value of the fixed point of  on

on  if there is a fixed point, else as false. Since

if there is a fixed point, else as false. Since  s are properties of arity

s are properties of arity  , there are at most

, there are at most  values for the

values for the  s, so with a polynomial-space counter we can check if there is a loop or not.

s, so with a polynomial-space counter we can check if there is a loop or not.

It has been proven that FO(PFP) is equal to PSPACE. This definition is equivalent to FO( ).

).

Least Fixed Point is P

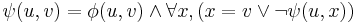

FO(LFP) is the set of boolean queries definable in FO(PFP) where the partial fixed point is limited to be monotone. That is, if the second order variable is  , then

, then  always implies

always implies  .

.

We can guarantee monotonicity by restricting the formula  to only contain positive occurrences of

to only contain positive occurrences of  (that is, occurrences preceded by an even number of negations). We can alternatively describe LFP(

(that is, occurrences preceded by an even number of negations). We can alternatively describe LFP( ) as PFP(

) as PFP( ) where

) where  .

.

Due to monotonicity, we only add vectors to the truth table of  , and since there are only

, and since there are only  possible vectors we will always find a fixed point before

possible vectors we will always find a fixed point before  iterations. Hence it can be shown that FO(LFP)=P. This definition is equivalent to FO(

iterations. Hence it can be shown that FO(LFP)=P. This definition is equivalent to FO( ).

).

Transitive closure is NL

FO(TC) is the set of boolean queries definable in FO with a transitive closure (TC) operator.

TC is defined this way: let  be a positive integer and

be a positive integer and  be vector of

be vector of  variables. Then TC(

variables. Then TC( is true if there exist

is true if there exist  vectors of variables

vectors of variables  such that

such that  , and for all

, and for all  ,

,  is true. Here,

is true. Here,  is a formula written in FO(TC) and

is a formula written in FO(TC) and  means that the variables

means that the variables  and

and  are replaced by

are replaced by  and

and  .

.

This class is equal to NL.

Deterministic transitive closure is L

FO(DTC) is defined as FO(TC) where the transitive closure operator is deterministic. This means that when we apply DTC( ), we know that for all

), we know that for all  , there exists at most one

, there exists at most one  such that

such that  .

.

We can suppose that DTC( ) is syntactic sugar for TC(

) is syntactic sugar for TC( ) where

) where  .

.

It has been shown that this class is equal to L.

Normal form

Any formula with a fixed point (resp. transitive cosure) operator can without loss of generality be written with exactly one application of the operators applied to 0 (resp.  )

)

Iterating

We will define first-order with iteration, 'FO[ ]'; here

]'; here  is a (class of) functions from integers to integers, and for different classes of functions

is a (class of) functions from integers to integers, and for different classes of functions  we will obtain different complexity classes FO[

we will obtain different complexity classes FO[ ].

].

In this section we will write  to mean

to mean  and

and  to mean

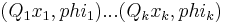

to mean  . We first need to define quantifier blocks (QB), a quantifier block is a list

. We first need to define quantifier blocks (QB), a quantifier block is a list  where the

where the  s are quantifier-free FO-formulae and

s are quantifier-free FO-formulae and  s are either

s are either  or

or  . If

. If  is a quantifiers block then we will call

is a quantifiers block then we will call ![[Q]^{t(n)}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a927826b8dcb6e581cff78622f73cf2b.png) the iteration operator, which is defined as

the iteration operator, which is defined as  written

written  time. One should pay attention that here there are

time. One should pay attention that here there are  quantifiers in the list, but only

quantifiers in the list, but only  variables and each of those variable are used

variables and each of those variable are used  times.

times.

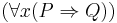

We can now define FO[ ] to be the FO-formulae with an iteration operator whose exponent is in the class

] to be the FO-formulae with an iteration operator whose exponent is in the class  , and we obtain those equalities:

, and we obtain those equalities:

- FO[

] is equal to FO-uniform ACi, and in fact FO[

] is equal to FO-uniform ACi, and in fact FO[ ] is FO-uniform AC of depth

] is FO-uniform AC of depth  .

. - FO[

] is equal to NC.

] is equal to NC. - FO[

] is equal to PTIME, it is also another way to write |FO(LFP).

] is equal to PTIME, it is also another way to write |FO(LFP). - FO[

] is equal to PSPACE, it is also another way to write FO(PFP).

] is equal to PSPACE, it is also another way to write FO(PFP).

Logic without arithmetical relations

Let the successor relation, succ, be a binary relation such that  is true if and only if

is true if and only if  .

.

Over first order logic, succ is strictly less expressive than <, which is less expressive than +, which is less expressive than bit. + and  are as expressive as bit.

are as expressive as bit.

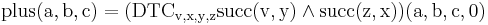

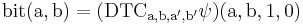

Using successor to define bit

It is possible to define the plus and then the bit relations with a deterministic transitive closure.

and

and

with

with

This just means that when we query for bit 0 we check the parity, and go to (1,0) if  is odd(which is an accepting state), else we reject. If we check a bit

is odd(which is an accepting state), else we reject. If we check a bit  , we divide

, we divide  by 2 and check bit

by 2 and check bit  .

.

Hence it makes no sense to speak of operators with successor alone, without the other predicates.

Logics without successor

On logic without succ, +,  , < or bit, the equality becomes that FO(LFP) is equal to relational-P and FO(PFP) is relational-PSPACE, the classes P and PSPACE over relational machines.[2]

, < or bit, the equality becomes that FO(LFP) is equal to relational-P and FO(PFP) is relational-PSPACE, the classes P and PSPACE over relational machines.[2]

The Abiteboul-Vianu Theorem states that FO(LFP)=FO(PFP) if and only if FO(<,LFP)=FO(<,PFP), hence if and only if P=PSPACE. This result has been extended to other fixpoints.[2] This shows that the order problem in first order is more a technical problem than a fundamental one.

References

- Ronald Fagin, Generalized First-Order Spectra and Polynomial-Time Recognizable Sets. Complexity of Computation, ed. R. Karp, SIAM-AMS Proceedings 7, pp. 27–41. 1974.

- Ronald Fagin, Finite model theory-a personal perspective. Theoretical Computer Science 116, 1993, pp. 3–31.

- Neil Immerman. Languages Which Capture Complexity Classes. 15th ACM STOC Symposium, pp. 347–354. 1983.

- ^ N. Immerman Descriptive complexity (1999 Springer)

- ^ a b Serge Abiteboul, Moshe Y. Vardi, Victor Vianu: logics, relational machines, and computational complexity Journal of the ACM (JACM) archive, Volume 44 , Issue 1 (January 1997), Pages: 30-56, ISSN:0004-5411

External links

- Neil Immerman's descriptive complexity page, including a diagram

- zoo about FO, see the class under it also